Basic knowledge of wildfires is essentially a narrow segment of trigonometry, focusing on the study of triangles. The fundamental principles describing wildfires are represented by two key triangles, known as the fire triangle, which everyone seeking to understand the nature of landscape fire should know. The first triangle explains the essence of fire itself, while the second describes its behavior. This approach to presenting information on the physicochemistry of combustion and fire behavior condenses the subject into three key aspects.

.

Table of Contents

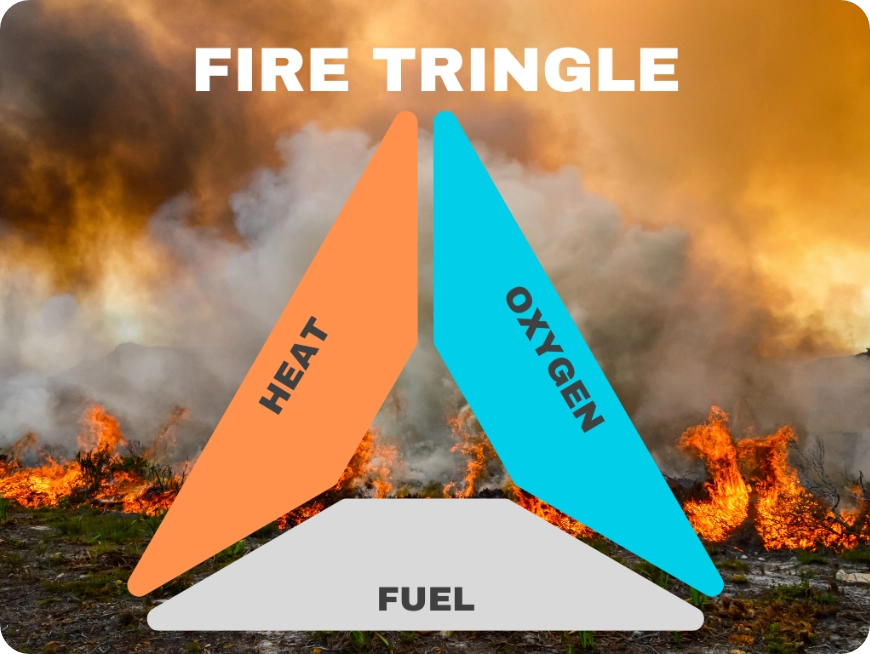

ToggleThe Fire Triangle

The first model simply describes the physicochemical reaction of combustion, making it easier to understand the essential components required for fire to occur. For combustion to take place, fuel must be heated to its ignition temperature and mixed with an oxidizer at the right concentration. The fire triangle illustrates this relationship – each of its sides represents one of these elements. If any of them is missing, the triangle cannot form, and combustion will not occur. Fire emerges when all three factors interact in time and space. It can be extinguished, limited, or prevented by eliminating, reducing, or separating one of its components.

.

.

Heat

Heat is essential for igniting fire. It can come from various sources, and in the case of wildfires, we refer to the cause. For more information on what causes wildfires, you can visit this blog post . Once ignited, the fire generates heat on its own, sustaining combustion and accelerating its spread. Heat removes moisture from the fuel, warms the air, and heats up materials in the path of the flames. Without heat, the forest would only have fuel and an oxidizer—i.e., trees and atmospheric oxygen. It is the presence of an energy trigger with a certain power, capable of initiating combustion, that brings blaze to the forest.

.

Oxidizer

The air contains about 21% oxygen, and at least 16% is sufficient to sustain combustion. There is enough of it to allow a fire to start as long as the other two components of the triangle are present. In landscape fires, which develop in open spaces, there are no physical barriers limiting oxygen access, allowing the flames to spread quickly. Oxygen acts as the oxidizer, and without it, fire would not exist. It aids in combustion, and the right amount of oxygen makes the flames burn brighter, hotter, and faster. It also helps break down fuel molecules into flammable compounds, releasing energy and heat while also mixing with the gases released from the fuel to create a flammable gas mixture.

.

Fuel

There is no smoke without fire, just as there is no fire without fuel. In order for a fire to start, a flammable material must burn, i.e. fuel – any substance that will ignite under the influence of heat and oxygen. In the case of wildfires, fuel is any plant material (living or dead) that can burn in a fire. Its availability determines whether the fire will continue. Natural fuels contain moisture, which initially protects them from ignition. For a fire to begin, the fuel must dry out. The water inside the material extends the drying time to a level where ignition is possible. When the fuel is heated to the appropriate temperature, it thermally decomposes and releases volatile gases. The fuel then combines with oxygen in a combustion reaction, producing heat and other combustion products.

.

Fire Behavior Triangle

Understanding fire behavior is crucial for firefighters and land managers in fire-prone areas. Fire in the landscape is not random – its development depends on the interaction of several factors. To facilitate their analysis, the Fire Behavior Triangle model was developed to explain fire dynamics. This triangle consists of three elements: fuel, weather conditions, and topography. Each of these factors influences the speed, direction, and intensity of the fire. Their interaction means that even a small change in one of these factors can significantly impact the fire’s development.

.

.

.

Fuel

Fuel is a common element in both fire triangles because without it, fire cannot start or spread. Just as a car cannot run without fuel, a fire will extinguish when there is no material to burn. Importantly, fuel is the only factor that humans can control – managing vegetation allows for reducing the risk of fires before they occur and also influences their course and impact. The characteristics of fuel are crucial to the dynamics of a fire. Different types of vegetation burn in different ways – plants rich in resins and essential oils intensify flames, scattering sparks, while others may slow their spread. The chemical composition of the fuel affects its ease of ignition and the intensity of combustion. The most important factor in flammability is moisture content. Living plants store water, which slows combustion since the fire must first evaporate the moisture. In contrast, dead, dried plant parts ignite much faster, providing ideal fuel for a fire. The amount, distribution, and density of fuel are also significant. To fully understand how these factors affect fires, it’s essential to know the biology of species and the functioning of ecosystems. This topic was discussed in more detail in a previous blog post – Understanding Wildfires.

.

Meteorological Conditions

Weather is the most variable factor in the fire behavior triangle, affecting its intensity, rate of spread, and scale of destruction. However, fire analysis cannot rely on a single meteorological parameter, as it is the result of the interaction of multiple factors. Wind drives the fire, directing it toward new fuel, increasing the supply of oxygen, and drying out the combustible material. It can also carry glowing embers ahead of the main fire line, creating new fire hotspots. Temperature also plays a crucial role – the higher it is, the faster the fuel loses moisture, making ignition easier. Air humidity above 70% significantly slows down fire spread, and moist obstacles can alter its rate of spread. In extreme conditions, wildfires can even generate their own weather phenomena, complicating control efforts.

.

Topography

The impact of topography on fire behavior is more predictable than the other elements of the fire triangle. Fire spreads more quickly uphill, and the steeper the slope, the more intense the burning. This phenomenon can be further intensified by wind blowing uphill. Terrain exposure affects sunlight – southern slopes, which are more exposed to the sun, have higher temperatures, lower humidity, and drier fuels, making them more prone to fires. Elevation also plays a role – at lower altitudes, fuels dry out more quickly, while in the mountains, snow can delay the fire season. Additionally, landforms such as valleys and ridges can alter wind patterns, speeding up airflow and enhancing the fire’s intensity.

The above triangles are a great simplification of the complex knowledge about wildfires, which in both cases makes it easy to remember the three key factors. Their joint analysis shows how crucial fuel is in the entire process. Understanding both triangles is essential for preventing fires, effectively extinguishing them, and predicting their behavior in different conditions.